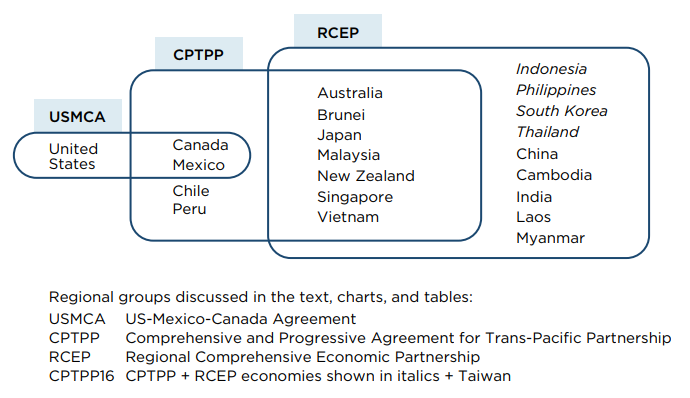

Trade Agreements

Latest Updates

View More

About CPTPP and RCEP

About CPTPP

What is the Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership (CPTPP)?

The Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership (CPTPP) is a 21st century, comprehensive, multilateral free trade agreement between 11 countries: Australia, Brunei, Canada, Chile, Japan, Malaysia, Mexico, New Zealand, Peru, Singapore, and Vietnam.

After President Donald Trump withdrew the United States from the original Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP) in January 2017, the remaining 11 signatories, known as the TPP-11, successfully developed a new trade agreement without the U.S.: the CPTPP. The CPTPP was signed in Chile in March 2018 and entered into force on December 30, 2018. Members of the CPTPP cover a combined 13.5% of the global economy, making this one of the largest free trade agreements in the world.

Most provisions of the CPTPP are similar or identical to the original TPP. However, 22 provisions of the TPP that were once favored by the U.S. but generally opposed by other signatories were suspended in the CPTPP. One of the main differences in the CPTPP is the removal of certain provisions regarding intellectual property. Though the U.S. favored longer copyright terms, automatic patent extensions, and separate protections for new technologies, these provisions were unpopular among the remaining signatories and ultimately removed from the CPTPP. The CPTPP also features modifications to the investment chapter, certain implementation timelines, and labor and environmental rules from the original TPP. These suspended provisions, however, can also be reinstated, leaving the door open for the U.S. to join the agreement.

The withdrawal of the U.S. did indeed have a considerable impact on the effects of the trade agreement, reducing the global income gains from the agreement by 70%. Yet, even without the U.S., the CPTPP still creates real income gains of approximately 1% of GDP for CPTPP countries. The Peterson Institute for International Economics estimates that the CPTPP will add an estimated $147 billion to global income. The CPTPP provides crucial trade and investment liberalization and reforms, boosting productivity and business opportunities in member countries.

Entry into Force and Status of Ratification

Once signed in March 2018, the CPTPP needed six participating countries to ratify the agreement to bring it into effect. As of May 2019, seven countries have ratified the CPTPP: Australia, Canada, Japan, Mexico, New Zealand, Singapore, and Vietnam. The agreement entered into force between these seven countries on December 30, 2018 but has yet to enter into force for the remaining four signatories – Brunei, Chile, Peru, and Malaysia – that have not yet ratified the agreement.

Key Features

- Comprehensive market access: to eliminate tariffs and other non-tariff barriers to a wide a range of goods and services trade and investment, so as to create new opportunities for workers and businesses and immediate benefits for consumers. The CPTPP eliminates an estimated 95% of tariffs for trade of goods between CPTPP countries.

- Fully regional agreement: to facilitate the development of production and supply chains among CPTPP members, supporting a goal of creating jobs, raising living standards, improving welfare and promoting sustainable growth in member countries.

- Cross-cutting trade issues: to build on work being done in APEC and other fora by incorporating several cross-cutting issues. These include:

- Regulatory coherence. Commitments encourage the use of widely accepted, good regulatory practices and facilitates coordination within CPTPP members’ governments.

- Competitiveness and Business Facilitation. Commitments enhance the domestic and regional competitiveness of each CPTPP country’s economy and promote economic integration and jobs in the region, including through the development of regional production and supply chains.

- Small- and Medium-Sized Enterprises. Commitments address concerns that small- and medium-sized enterprises have raised about the difficulty in understanding and using trade agreements, encouraging small- and medium-sized enterprises to trade internationally.

- Development. Comprehensive and robust market liberalization, improvements in trade- and investment-enhancing disciplines, and other commitments, including a mechanism to help all CPTPP countries to effectively implement the Agreement and fully realize its benefits, will serve to strengthen institutions important for economic development and governance and thereby contribute significantly to advancing CPTPP countries’ respective economic development priorities.

- Government Procurement. Commitments address barriers in government procurement, allowing companies of CPTPP countries to have more opportunities to bid for government projects that were previously unavailable to foreign bidders.

- Addresses new trade challenges: to promote trade and investment in innovative products and services, including those related to the digital economy and green technologies, and to ensure a competitive business environment across the CPTPP region.

- Living agreement: to enable the updating of the agreement as appropriate to address trade issues that emerge in the future as well as new issues that arise with the expansion of the agreement to include new countries.

The Future of the CPTPP in ASEAN

The CPTPP is open to accession by other countries, including the U.S. and other Southeast Asian nations, though the process may be lengthy due to the high standards included in the agreement. Beyond the existing signatories of the CPTPP in ASEAN, Thailand, Indonesia, and the Philippines have expressed interest in joining the CPTPP. Adding more economies to the CPTPP could multiply the benefits of the agreement. According to the Peterson Institute for International Economics, if Indonesia, Korea, Philippines, Taiwan, and Thailand entered the CPTPP, the benefits would increase three-fold. The addition of these five countries to the agreement would yield an estimated $449 billion per year in global income gains, in comparison to the $147 billion annual benefits generated by the current agreement. Increasing CPTPP membership would spur greater regional economic integration and supply chains across the Asia-Pacific region.

About RCEP

The Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP) is another proposed free trade agreement involving many of the same countries as the CPTPP. 16 countries have been negotiating the RCEP with the goal of broadening and deepening trade ties in the Asia-Pacific region. All 10 ASEAN countries – Brunei, Cambodia, Indonesia, Laos, Malaysia, Myanmar, the Philippines, Singapore, Thailand, and Vietnam – are involved in the negotiations, along with six ASEAN free trade partners in the region: Australia, China, India, Japan, South Korea, and New Zealand. The countries comprising the RCEP account for approximately 30% of global GDP and have a collective population of over three billion people, which would make the RCEP the largest FTA in the world. Objectives and guiding principles for negotiating the RCEP may be found here. RCEP negotiations were launched in late 2012 but have yet to conclude.

On November 12, 2018, economic ministers gathered during Singapore’s ASEAN Chairmanship to achieve a “substantial conclusion” of RCEP negotiations in time for the ASEAN leaders’ meeting. It appears that some flexibility was requested to delay conclusion in view of four elections in 2019 -India, Indonesia, Thailand, and the Philippines. The signing and ratification of free trade agreements could be politically difficult and challenging for governments. To date, only seven of the eighteen “chapters,” or major negotiation topics, have been agreed to: Economic and Technical Cooperation, Small and Medium Enterprises, Customs Procedures and Trade Facilitation, Government Procurement, Institutional Provisions, Sanitary and Phytosanitary Measures, and Standards, Technical Regulations and Conformity Assessment Procedures. A copy of the 2018 Joint Leaders Statement is available here.

The main difference between the RCEP and the TPP, however, is that the RCEP does not contain major commitments on labor, the environment, intellectual property, state-owned enterprises, and many other issues addressed in the original TPP and the CPTPP. For example, it remains to be seen whether the RCEP e-commerce chapter, expected to be concluded this year, will be any closer to CPTPP.

Strategic Interests of Participating US and Southeast Asian Economies

U.S. Interests in the CPTPP

In recent years, specifically under the Trump administration, the United States has shifted its focus to bilateral free trade agreements (FTAs) that would eliminate or reduce bilateral trade imbalances. These agreements, however, provide limited economic benefits to the United States and do not provide the same catalyst for regional production networks in the Asia-Pacific region as multilateral FTAs do. Within ASEAN, the U.S. bilateral FTA negotiations with Malaysia and Thailand have reached a standstill. Additionally, if reached, a bilateral agreement between the U.S. and Japan would only provide a fraction of the benefits of the original TPP.

The Peterson Institute for International Economics estimates losses of $133 billion annually for the United States due to withdrawal from the TPP and subsequent foregone trade opportunities. This estimate includes the $131 billion that the U.S. would have gained from the original TPP, as well as the $2 billion in losses the U.S. incurs without CPTPP membership. Michael Froman, who served as the U.S. Trade Representative under President Obama, said that the American exporters are facing negative consequences as a result of the U.S. pulling out of the TPP. In Japan, the third largest economy in the world, the U.S. agriculture industry has been at a disadvantage to countries that have free trade agreements with Japan. For example, Australian beef and Chilean wine dominate their respective markets in Japan due to substantially lower duties than American products. Joining the CPTPP would not only alleviate the disadvantages faced by American exporters but would significantly boost the global gains from the CPTPP.

Japan, Malaysia, and Vietnam would be the primary beneficiaries of U.S. membership to the CPTPP, as these countries had pre-existing FTAs with many of the signatories. These countries had the most to gain from access to U.S. markets offered under the TPP.

By withdrawing from the TPP, the U.S. also began to lose its status as the international trade rule-maker. Since many CPTPP members use the agreement as a model in negotiating new FTAs, the CPTPP plays an important role in FTA standards. Though the United States-Mexico-Canada Agreement (USMCA) did help the U.S. reassert itself as a trade rule-maker, returning to the CPTPP would amplify this and strengthen U.S. influence in the Indo-Pacific region in relation to China.

Positions of Participating ASEAN Member States

Brunei

As one of the 4 original members of the P-4 group, the Government of Brunei viewed the TPP as a policy instrument which could help promote economic diversification in Brunei. Since Brunei has not yet ratified the CPTPP, the agreement has not taken effect in the country. Brunei’s Second Finance and Economy Minister Amin Liew Abdullah recognized the benefits of both the CPTPP and the proposed Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP) for Brunei, citing trade liberalization, trade rules, progressive reforms, and regional integration. In addition, Brunei continues to explore ways of leveraging its participation in the RCEP negotiations as catalysts for supporting economic diversification.

Malaysia

Since Malaysia has not yet ratified the CPTPP, the agreement has not taken effect in the country. Historically, open trade policies have boosted Malaysia’s economic growth, and ratification of the CPTPP would do the same. The agreement benefits palm oil, rubber, and electronics exporters in Malaysia by providing access to new markets, such as Canada and Mexico. Conversely, not ratifying the CPTPP could hurt Malaysia’s export and FDI competitiveness. Though Prime Minister Mahathir Mohamad previously expressed support for the CPTPP, support for the agreement throughout Malaysia has declined under his administration, with many lawmakers in the leading Pakatan Harapan coalition expressing concerns about its effects. Some fear that the ratification of the CPTPP will reduce policy flexibility and limit the preferences that government-linked companies can offer to local small- and medium-size enterprises. There is, however, also some pressure within Malaysia to ratify the CPTPP. Though ratification does not appear to be a priority for the Malaysian government, the administration has not completely written it off. In January 2019, Minister of International Trade and Industry Darell Leiking said the administration was still reviewing the terms of the agreement to ensure that it is fair to Malaysia and reported that there was nothing stopping the government from ratifying it.

On the other hand, concluding the RCEP negotiations is a top priority for Malaysia, with hopes that the agreement will be concluded by the end of 2019.

Singapore

The CPTPP creates new trade agreements for Singapore with Japan, Australia, New Zealand, Chile, and Peru. It is also Singapore’s first trade agreement with Canada and Mexico, expanding market access for Singapore companies. Given its reliance on exports, Singapore stands to achieve major gains from this enhanced market access and preferential tariffs when exporting to other CPTPP countries. Specifically, 94% of Singapore’s trade with other CPTPP countries will be tariff-free immediately upon the agreement’s entry into force, with the remaining tariffs set to be eliminated in the future. Minister for Trade and Industry Chan Chun Sing cited estimates that the CPTPP will boost Singapore’s economy and total exports by 0.2 percent more each by 2035. Further, with the new guidelines for government procurement, Singapore companies will be able to bid for government projects in Malaysia, Mexico, and Vietnam, all of which were closed to foreign bidders prior to the CPTPP. Singapore also supports the accession of new countries to the agreement, recognizing that this would enhance regional economic integration and provide greater economic benefits.

Singapore continues to play an important role in the negotiation of the RCEP. Prime Minister Lee Hsien Loong expressed his hopes that the agreement will be concluded in 2019, though this is ambitious given how much needs to be accomplished by then.

Vietnam

Vietnam is expected to be one of the main winners of the CPTPP. The World Bank conservatively estimates that the CPTPP will increase Vietnam’s GDP by at least 1.1% by 2030. This boost to the country’s GDP is due to an increase in exports, FDI, and productivity growth as a result of trade liberalization and expanded market access under the CPTPP. This agreement strengthens trade between Vietnam and Japan, with Vietnam’s exports Japan significantly increasing in the first quarter of 2019. The CPTPP is also Vietnam’s first trade agreement with Canada, Mexico, and Peru. According to Vietnam’s Ministry of Agriculture, between January and April 2019 alone, Vietnam’s seafood exports to CPTPP countries increased by 15 percent compared to the same period the year prior, generating an additional US$502 million in revenue. Further, the National Centre for Socio-Economic Information and Forecasting in Vietnam estimates that the CPTPP will boost the country’s exports by 4.04%, approximately US$4 billion, by 2035. Economists also predict that the agreement will serve as a catalyst for domestic reforms across a variety of sectors in Vietnam, such as improving regulations and investing more in innovation.

Similar to other ASEAN countries, Vietnam has high expectations for RCEP’s positive impact on Vietnamese imports and exports and aims to finalize the agreement in 2019.